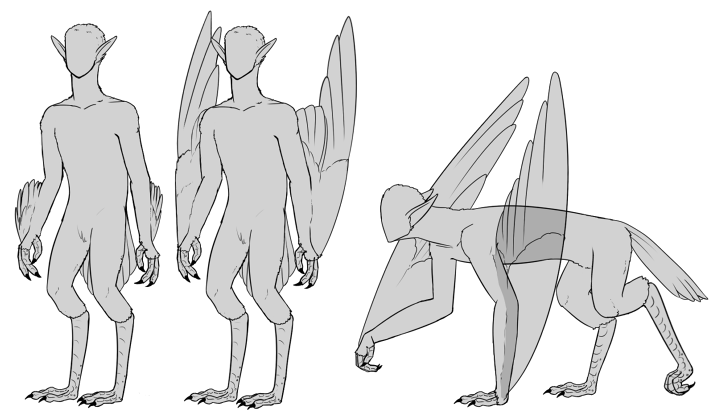

Ollphéan are large, bird-like creatures with strange faces and long necks. They have very flexible bodies, with proportions that seem to always be a bit too lanky to make sense. They are completely covered in feathers save for their faces and limbs, though many also show feathering all the way down to their "hands" on the forelegs. Said hands are opposable toes--usually three, occasionally four--with sharp talons. These toes, as well as the bare back legs, have a rough, cracked skin texture. Attached at the wrists are wings--sometimes large enough to be functional, sometimes just a smattering of slightly longer feathers than that of the ones on the body. Wing size appears to be determined partially by habitat; those with more space to move are more likely to grow flight feathers. Another cause of wing size may be due to excessive societal plucking negatively impacting offspring. Whether their wings work or not, all of them are born with hollow bones conducive for flight. Their ears and tails are also feathered, though the length and amount of feathers varies from bird to bird.

Ollphéan are not sexually dimorphic; all of them display the same musculature and reproductive traits.

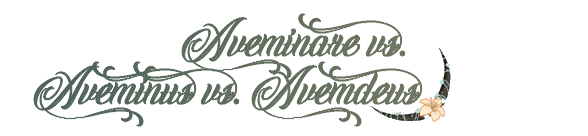

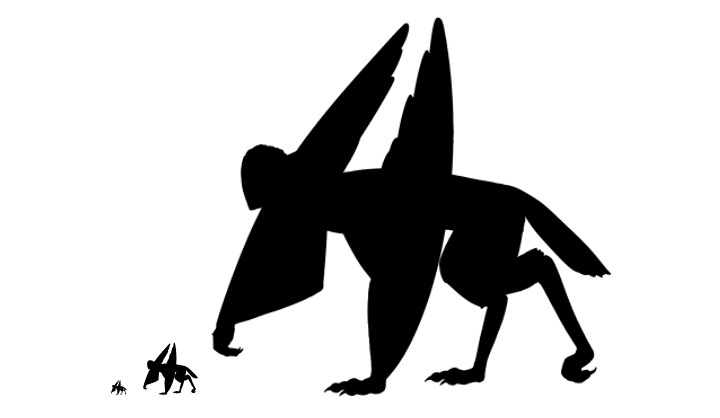

Despite there being three distinct size categories, not much appears to change from order to order. Aveminare range from four feet to eight, with eight being the cut off point where they begin to distinguish themselves as different orders. The average height for smaller birds is in the six foot range. The Aveminus have a much wider variety in their heights. The smaller ones are eleven feet, and the largest grow up to thirty. The average is in the twenty to twenty three area. The jump from Aveminare to Avemdeus is by far the largest, with Avemdeus being 500 feet and up. Avemdeus may appear more feral than other birds, but their physical features are fairly similar to their smaller counterparts.

Ollphéan spend the majority of their time on all fours, backs slightly hunched, but many have the ability to stand on their back feet and walk for short distances. Their long back legs tuck up under their bodies when in flight and when nesting. All birds have flat chests and haunches built wide enough for egg laying. Their ears swivel to face noises they find particularly interesting, and their feathers are able to fluff to display emotion. A full body fluff is a sign of happiness, while only raising the feathers along the back shows indignation. All birds also go through a molt once a year. Usually in the fall, birds will slowly drop all their feathers and re-grow them over the course of a month. They often become itchy and irritable, searching out bodies of water to soak in to ease the irritation.

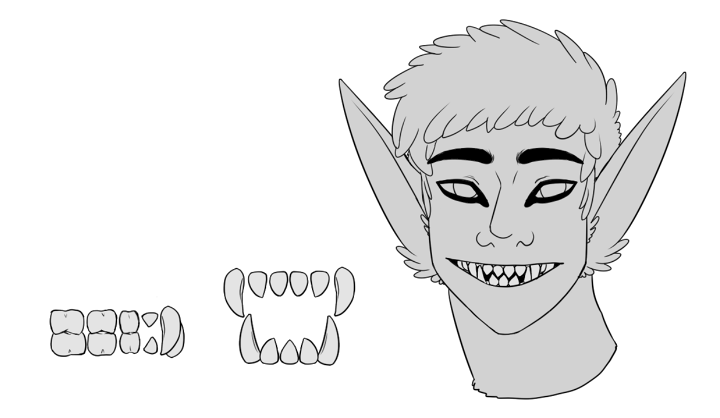

Their bones are hollow, so even the heaviest bird is lighter than they look. Their featherless feet have opposable fingers that allow them to grasp, use tools, and make complicated gestures. Ollphéan have very sharp eyesight, with decent to exceptional night vision. Their pupils are slits, and expand in low light or when aroused. Their vocal chords are able to produce a seemingly endless number of vocalizations, including: chirps, purrs, hums, speech, singing, imitations of other noises, growls, and whistles.

Ollphéan are omnivorous, and their teeth are equipped to handle anything they may attempt to eat. Their front teeth and canines are sharp, designed to tear meat, and the rest are flat, designed to grind fruits and vegetables and crush insects.

Ollphéan come in an incredibly diverse variety of colors and patterns. There does not seem to be a color that can't be found in their palette of feathers. Offspring can inherit any manner of traits from their parents, and often end up either looking like an even split of the two, or having their appearance lean heavily in one direction with only a few scattered traces of the other parent. Each species has the ability to successfully breed with the rest. Most Ollphéan are a mix of four or more different species by now, even if distantly; "purebreds" are all but extinct.

Their skin and eyes come in as many colors as their feathers do. The feathers along the head and down the neck are softer than the ones covering the body or that make up the wings. Many birds "style" these feathers, effectively creating different "hair-dos". The crest feathers can be trimmed, grown out, pushed back, pulled up, and are sometimes even altered with temporary dyes made from natural pigments.

While gorgeous and useful in catching a special bird's eye, brightly colored plumage poses a distinct disadvantage to smaller birds, as any Aveminare looking to hide from an Aveminus is going to be much easier to spot the more elaborate their coloring. However, since much of the breeding is controlled by Aveminus, pet-sized birds rarely have a choice when it comes to picking mates with dull enough colors to ensure a more camouflaged child.

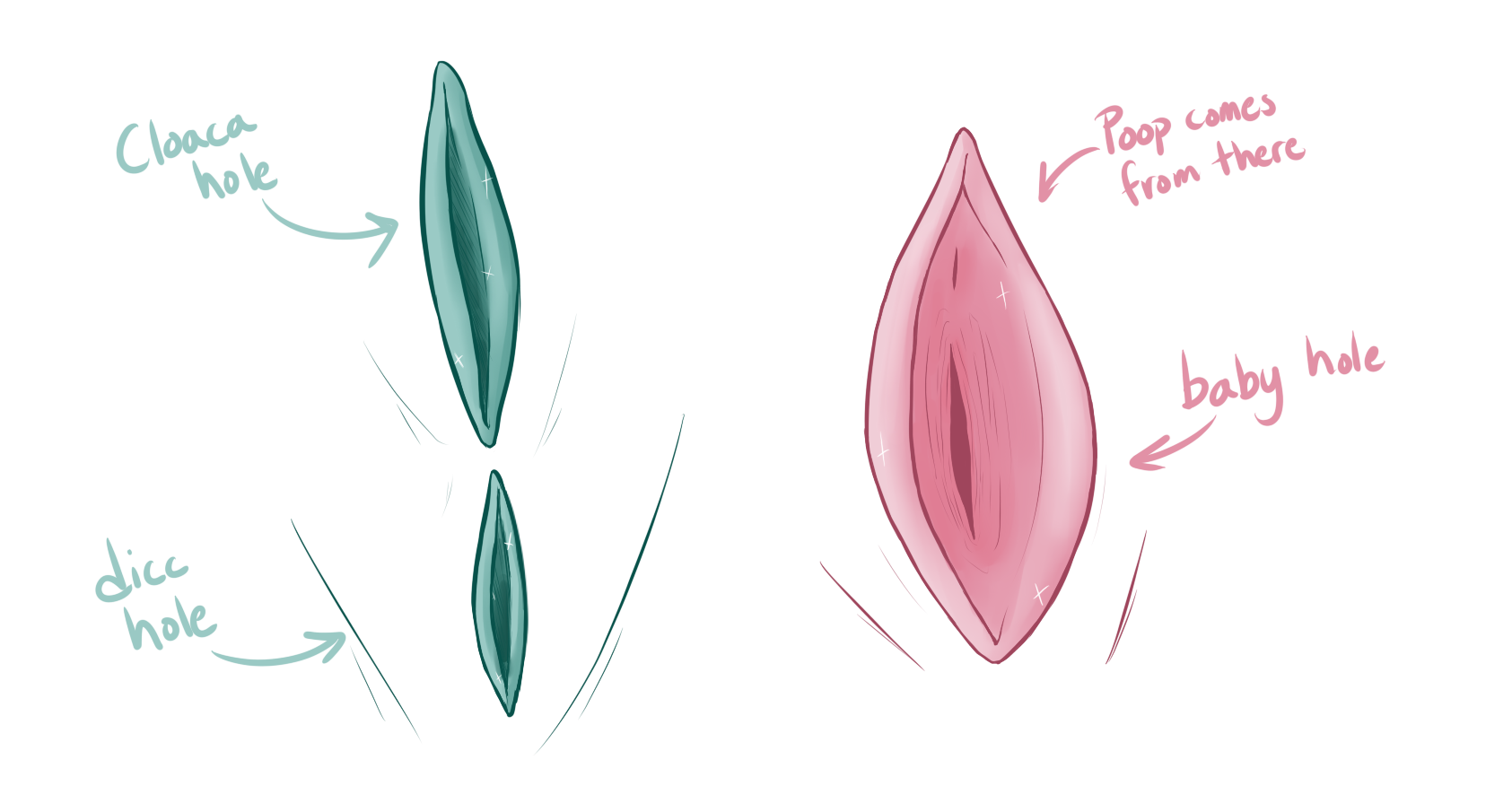

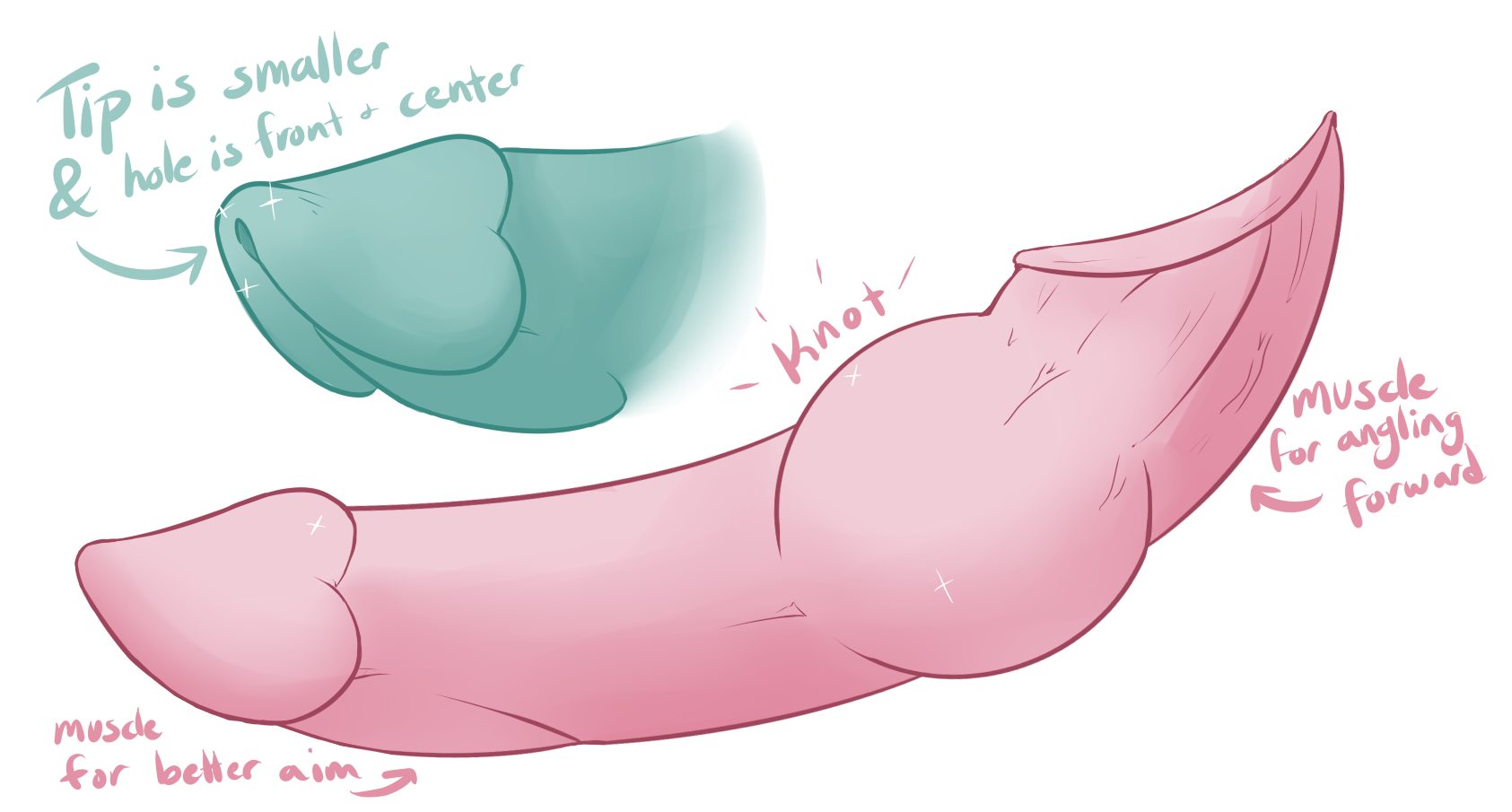

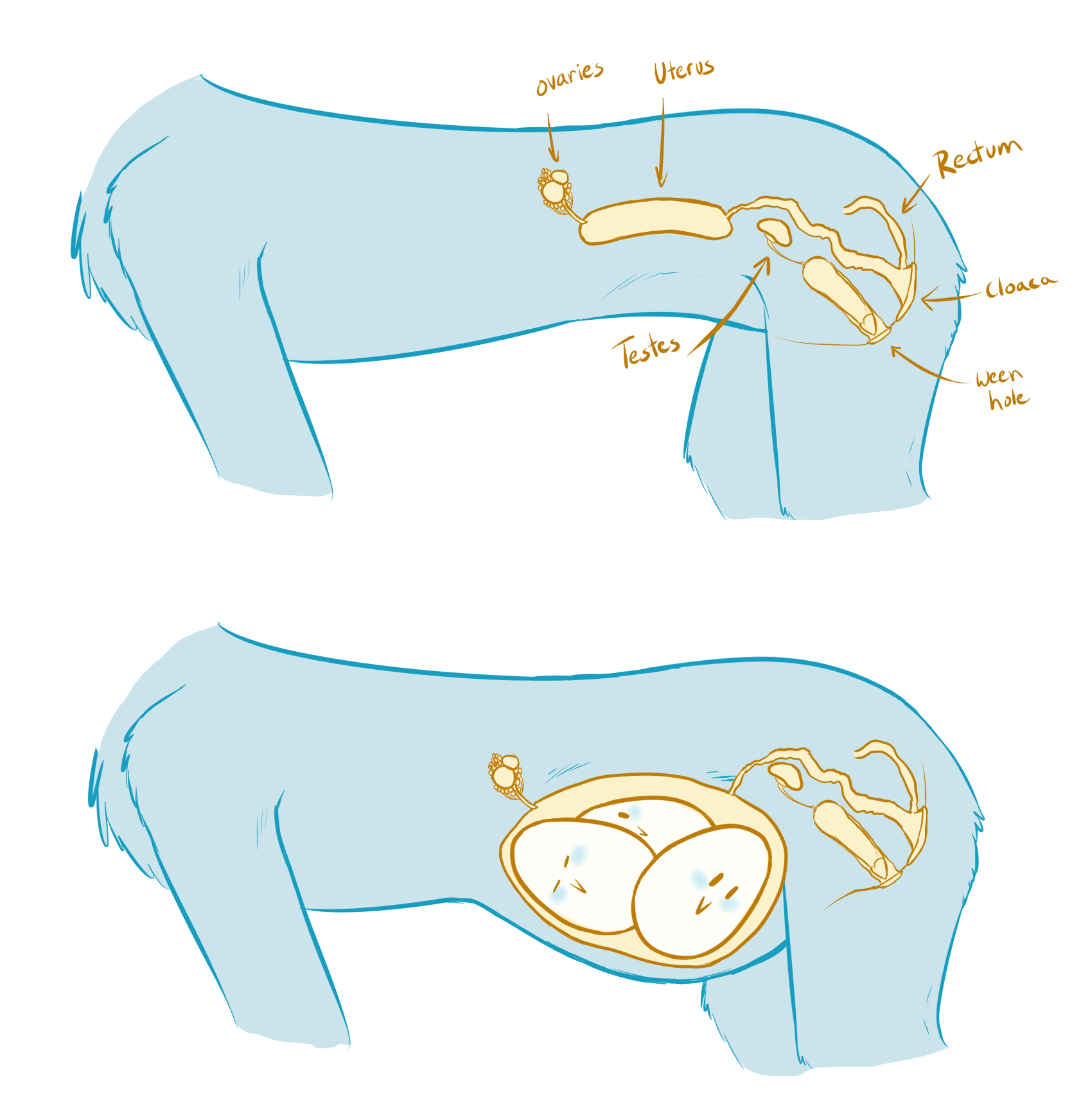

Ollphéan all have cloaca containing the same genitalia. Each bird has a penis and a vagina, and is capable of laying eggs. The maximum amount of eggs an Ollphéan can lay at a time is three, but there is no guarantee that all--or any--of the eggs will be fertile. Ollphéan do not lay without sexual contact; they must be sexually stimulated to produce eggs.

NSFW. Click for illustrations. »

All birds experience a monthly heat where fertility is at its highest, with the most potent heats always coinciding with the summer blooming of Freyja lilies (which increase fertility even further when consumed, increasing the chances of eggs with double yolks that produce true twins). These heats slow, and temporarily stop, during winter, but birds may still lay eggs. If a bird wishes to be sexually active without risking offspring, they can consume berrien roots, which, in Ollphéan terms, turns eggs "clear." This means that the eggs are sterile, and are usually eaten. Aveminus will often feed (sometimes by force) berrien roots to their Breeder pets before mating with them, ensuring a continuous, high protien food source.

Stress plays a part in an Ollphéan's reproductive health. Stressed birds may become eggbound, meaning their eggs might get stuck during laying and cause significant health problems. The size of the egg also varies slightly depending on the breeding pair. Master class birds may injure pet class birds during mating, and if they don't, there's always the chance the eggs will be larger than the Aveminare is ready to handle. Many birds will take homemade medications or alcohols to aid in relaxation during laying periods.

Gestation (the time it takes the egg to form before laying) is roughly six weeks, and incubation (the time it takes for the egg to hatch) lasts about four weeks. Chicks are born naked and with closed eyes, which open a few hours after hatching. Their skin tone and eye color are the only things apparent from birth. Colors and patterns are not apparent until the chick begins to grow their feathers at eight days old.

Birds are able to be impregnated as soon as three days after laying, but the pressure of gestating eggs while incubating eggs affects both clutches. The laid clutch may not get the warmth it needs, and the gestating clutch will be affected by the parent's stress hormones, resulting in lower chances of fertilized eggs.

Ollphéan have an incredible lifespan, with luckier ones being able to live up to 200 years.

By a hatchling's first year they are completely feathered, and by the time they are six they're able to speak, move, and eat on their own without relying on a parent to regurgitate for them. They are not yet fully grown at this age, but begin to leave the nest anyway. Growth spurts happen around their seventeenth year, and much of their height is gained then. For Masters, growth continues on until their late twenties, but for pets, growth is stunted at eighteen.

Eighteen is the age when a bird reaches sexual maturity and is able to begin laying with the right stimulus. It's also the age where they are first at risk for being picked up as a pet, though they are always in danger of being eaten. Masters will not bother to keep a bird that is not capable of reproducing, but age means nothing when it comes to meals.

Ollphéan are omnivorous, and will usually take advantage of whatever resources are available. Aveminare primarily eat insects, nuts, fruits, and berries, as even defenseless prey species are often too large for them to hunt without assistance. Smaller birds may form hunting parties in an attempt to satisfy their need for meat, but the majority of their protein intake comes from the generosity of Masters. Most large kills are managed by solitary Masters looking to feed their harem.

Kept pets in particular are scavengers, and will eat any discarded scraps left behind by a Master. It's a risky move, as sometimes the scraps eaten were purposely left out as a trap for other pets or prey. Aveminare will eat their own eggs in desperate times but it is frowned upon in the pet community, seen almost as blasphemy due to Masters keeping Breeders for the same purpose.

Aveminus have just as open of a diet as their smaller counterparts, however their size means they require a much larger quantity of food. This becomes troublesome thanks to their unwillingness to hunt cooperatively and the lack of availability when it comes to insects, nuts, fruits, and berries. If they haven't been lucky enough to come across decently sized prey, a Master may go on the hunt for wild pets. Snatching up a small bird or two is always easier than stalking and taking down an appropriately sized deer or elk, and prettier Aveminare may always be kept as new pets.